|

The

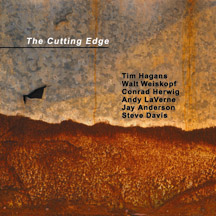

Cutting Edge - The Cutting Edge

Dtrcd-141

Tim Hagans - Trumpet

Walt Weiskopf - Tenor

Sax

Conrad Herwig - Trombone

Andy LaVerne - Piano

Jay

Anderson - Bass

Steve

Davis - Drums

1. Footprints

2. Yesterdays

3. Code Bleu

4. Canaloupe

Island

5. Cutting Edge

6. Secret Of The Andes

7. Space

Dozen

8. Our Destiny

9. Get Out Of Town

Total Time 64:52

|

"The Cutting Edge" comprises a program chock-a-block

with challenging originals and reharmonized standards, performed by a

collective sextet of world-class improvisers that was formed for this

session. Veteran pianist Andy Laverne, more than 40 musical projects

under his belt, stepped in to serve as acting music director, imparting

cohesion and flow to the proceedings. Not that the band -- elite

veterans of the New York scene who had crossed paths at various points --

needed much help finding common ground on which to operate.

"We have like minds in our

stylistic sensibilities with music," Laverne comments. "All of us,

in one way or another, are always looking to uncover new ways of

expressing music, and we're coming out of similar backgrounds at the core

of what influenced us, with the Miles Davis Quintet and John Coltrane

Quartet of the '60s as the starting point. Not that we're ignorant

of what preceded it by any means, but that's where we started our

formative years."

Let's hear Professor Laverne on

his cohorts: "Steve Davis has a lot of Elvin and Jack DeJohnette, but he's

melded both influences into a very unique style. He's definitely a

stylist, a colorist to the highest degree who can propel a band amazingly

and also engage in a lot of interplay, which is a great combination.

"Jay Anderson is bedrock,

unfailingly solid and dependable, with amazing ability as a soloist and a

capacity for rhythmic interplay. He isn't just a functional bass

player. He's always part of the ensemble while driving it forward."

Responding to a comment that

trumpeter Tim Hagans offers his own conclusions on prime-time Freddie

Hubbard, Laverne adds, "And Woody Shaw with a touch of Miles

perhaps. He's a strong individualistic player with an unusual way of

approaching changes. I've recorded a lot with Tim and he's played on

a bunch of my tunes, but I still have not been able to unlock his method

of playing over changes.

"Conrad Herwig is unusual also in

that, given the instrument he plays, he has similar sensibilities to

Tim. He's a very angular player. Though he'll do things that

are unique to the trombone, the larger picture of his conception,

harmonically and melodically, is influenced more by saxophonists and

pianists than by people who preceded him on that instrument -- more

Coltrane than J.J. Johnson or Curtis Fuller.

"Speaking of Coltrane, that's a

perfect segue to Walt Weiskopf, because he wrote one of the main books on

Coltrane ["Coltrane: A Player's Guide To Understanding His

Harmony"]. He's well-schooled and flexible, with a singular voice

that comes out of the Coltrane style, but unquestionably in his own

direction."

Some improvisers start off with

intense formal training before jazz grabs them; others start off with an

ear orientation, and come to theory later. "I was the former rather

than the latter," the 51-year-old Bronx native remarks. "I started

studying at Juilliard when I was 6, and was classically trained, not only

in playing the piano, but in theory and composition. I had a pretty

strong traditional harmony background before I ever got into jazz. I

was about 13 when I first heard jazz [Thelonious Monk's Monk's Dream], but

I had no understanding of it and the harmonic component completely

mystified me. That's probably one reason why I'm so harmonically

oriented and have done such extensive research and study and analysis, was

just trying to figure it out -- how to voice chords and so on.

"That's a major problem for

someone who's making the leap from Classical to Jazz, because the

vernacular is so different than in traditional harmony. For

instance, the use of Roman numerals is the way chords are expressed in

traditional harmony. You never see that in lead sheets; you only see

letter names without any function given to them other than if it's, let's

say, a dominant 7th or a minor 7th. In other words, if I saw a

progression in traditional harmony, it would be more specific and I would

kind of know how to play it. In jazz, you might see a G7 chord; you

can voice that a million different ways."

Laverne's approach to Herbie

Hancock's "Cantaloupe Island" and Wayne Shorter's "Footprints" -- iconic

landmarks of '60s composition -- is indicative of of his mature

conception. "'Cantaloupe Island' isn't a real radical

reharmonization," he notes. "I changed the last chord, and added

several bars. I based my comping on composite chords -- or

scale-tone chords -- which I've been developing lately. My goal with

recent reharmonizations is to freshen things up while keeping them still

quite familiar. My older reharmonizations were usually quite far

removed from the original.

"My version of 'Footprints' was

more influenced by Wayne's original version on 'Adam's Apple' than the

Miles Davis version. It's a disguised minor blues. At the end

of the first phrase I modulated down a half-step, and then reharmonized

the descending line at the end of the tune; I also changed some things in

the melody. Wayne is a very significant composer, because he's one

of the first who got away from functional harmony. He broke the

shackles of the II-V-I progression, and got into what's known as

'arbitrary root movement,' which led him to more colors than you hear in

traditional tunes based on Tin Pan Alley changes. Even when Wayne

was working in more familiar forms, his writing was so unique that it made

it unfamiliar.

"Herbie may have been less

radical than Wayne in his writing, but certainly no less radical in his

playing. They're both hard to pigeonhole, extremely flexible, and

their styles can cover a wide variety of music. They are hard to

duplicate also because they're not as codified as some other players,

maybe like Coltrane, who in certain ways had more structure. Wayne

and Herbie seem to be more extemporaneous."

A few years after Laverne heard

"Cantaloupe Island" ("I played it 8 billion times"), he embarked on

lessons with Bill Evans. "I was about 19, and by that point Bill was

pretty much all I listened to," he relates. "Whenever he played in

town, I was there every night. Once at the Vanguard I overheard him

telling someone he'd just moved into an apartment in Riverdale, where I

lived, and I somehow got up the courage to go up and speak to him.

As a result, I ended taking several lessons with him. Ultimately, I

think he was extremely effective, though by my current teaching standards

I would say he really didn't show me very much. He spoke more

conceptually, not about specific theoretical things -- voicings or scales

or the use or application of those things. I only realized fairly

recently that those lessons with Bill had the major impact on everything

that I do."

Laverne's writing displays a

rigorous intellect at the service of lyric, intense melodicism. To

wit, his arrangement of "Yesterdays". "It's an orchestration of an

arrangement I developed for a Maybeck solo recording a few years ago," he

explains. "In a nutshell, the ascending line at the beginning of the

tune I modulate up a minor third. then bring it back to the original key

at the end. It's a standard almost everybody has played at one point

or another, and I wanted to do something a little different.

"'Code Bleu' is a 12-bar blues

with slightly twisted harmonies -- not your standard I-IV-V blues.

"'Cutting Edge' was written to

match the title. Everyone on their instrument I think of as a

cutting edge player, and I tried to come up with something energetic that

the guys could really plug into. It went through several

incarnations melodically and harmonically, more complicated at first,

becoming simpler as it progressed. It's a 40-bar tune with a

repeated figure at the beginning, then goes through a set of V-I

progressions leading to a four-bar line over a descending whole-tone bass

line that leads back to C-minor."

"Secret of The Andes" was

previously recorded on "Modern Days And Nights," Laverne's previous

Double-Time recording, under the title "A Cole Porter Flat." "John

Patitucci gets credit for the title, though he probably doesn't know it,"

Laverne laughs. "It's in two sections, with a vamp in the beginning

that's actually part of the tune's form, and then the melodic part."

Tim Hagans offers the ingenious

"Space Dozen," a ominous blues based on a 12-note tone row that opens with

an imaginative polyphonic improvisation by the horns. "Tim wanted us

to play free, but be thinking of a blues, which we all tried to do,"

Laverne comments. "There are no chords; it's just a melodic line.

Conrad Herwig -- a long-time

Eddie Palmieri sideman whose "Latin Side of John Coltrane" from 1997

received much acclaim -- contributes the anthemic "Our Destiny."

Laverne comments: "It was great to play on this, because none of us were

able to bring the Latin feeling to the band as well as Conrad did.

Obviously, it's a lot of fun to play."

Walt Weiskopf's immediately

recognizable horn voicings mark his session-concluding arrangement of Cole

Porter's "Get Out of Town." "Walt's writing is almost like a

miniaturized big band," Laverne enthuses. "He's a more involved

arranger than I; he puts in lots of ensemble detail, whereas my writing is

more about harmonization."

With 40 dates under his sleeve,

where does "Cutting Edge" rank in Laverne's oeuvre? "I think it's

the first time that I've been at the helm of a sextet, so to speak," he

states. "It was nice to have the opportunity to work with three horn

players of this caliber in an ensemble setting like this, to have those

colors at my disposal."

What might a band like this

achieve in an ideal world, if they could tour several months a year?

"I think the possibilities would be unlimited," Laverne responds.

"There's so much creativity bundled up in this band, really the sky is the

limit. In terms of interpreting standards, jazz classics, and

certainly doing originals, this is merely the tip of the proverbial

iceberg."

Ted Panken - Sept.

‘99